Have you considered writing a family memoir? Your descendants will thank you.

Memory, I discovered, is a highly imperfect and malleable instrument

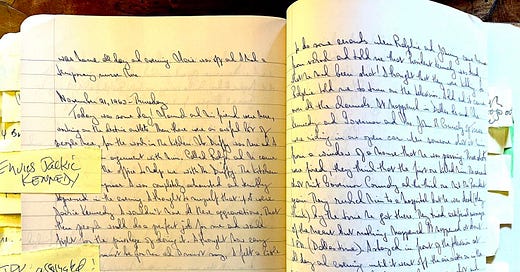

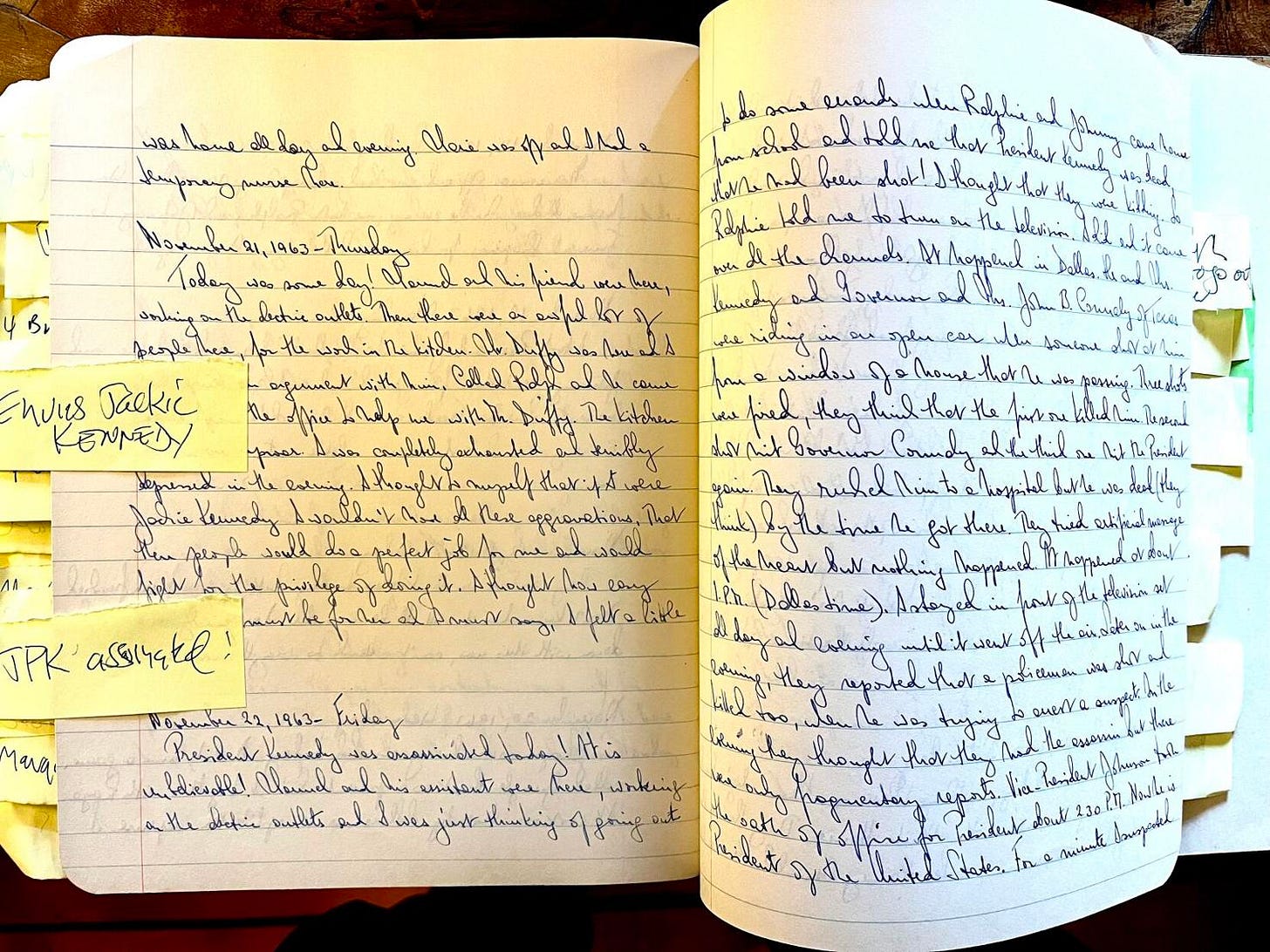

The page from the writer’s mother’s annotated diary for November 22, 1963, the date of President John F. Kennedy’s assassination

I’d humbly suggest that everyone try to write a memoir. There are several excellent reasons for doing so. You might find a publisher, though that’s probably a long shot. And you can always publish it yourself if the literary world frowns upon your achievement.

In a worst-case scenario, you’ve created a documentary record to leave behind for your children, your grandchildren and generations to come. But there’s an even better, more practical reason to put pen to paper, metaphorically speaking; keystrokes on laptops is more like it these days.

Memoir writing provides the mental equivalent of what morning exercises do for the body. It helps keep your mind limber. I’m working on one now and I’d like to think that keeping all the people, dates and stories straight is helping to stave off senility. I’m also getting lots of help, primarily from my mother. Sadly, she’s no longer with us. It’s not because she never penned a memoir, though I can’t help but think she’d have been sharper near the end if she had. However, she left behind a diary covering every day of her life starting in 1939, when she arrived in the United States from Europe ahead of World War II, and continuing through the late 1970s.

But that’s not all. She never threw anything away. If Robert Caro had a paper trail as extensive as I do he’d have completed the fifth and final volume of his magisterial biography of Lyndon Baines Johnson by now.

Nellie preserved virtually every letter, Christmas card, thank you note and telegram that she ever received. She even kept those cards included with floral arrangements. It’s no fun to be reminded of my mediocre record of academic achievement. But it’s the price one must pay because my mother retained every report card that my brothers and I received over the course of our undistinguished educational careers.

The worst part — or perhaps it’s the best part — is that I’ve followed in her footsteps. (My father was no deadbeat either when it came to recording his life for posterity.) I, too, have saved every holiday card classmates sent me, dating back to first grade. I have all my old bus passes. I’ve kept every letter I received from any woman I dated, included “Dear John” letters. I even have the notes that friends left on my college dorm room door — this was in the days before smartphones and message apps — informing me that they’d dropped by.

This Mount Everest of memorabilia is proving invaluable, or at least amusing, as I pursue my own efforts at memoir writing. It will also present a nightmare for my children when the time comes to dispose of it.

Suggestion to my kids: Rent a nearby storage locker. There’s no need to rush into a decision at your moment of maximum grief; I’m assuming they’ll be grieving, though their heartbreak may quickly transform to resentment once they realize how much junk I’ve left behind. A storage space will allow them to examine my archives, not to mention those of my parents, at their leisure.

That’s what happened to me after my mother passed away and more than a hundred years of family history, if you include my grandparents and their artifacts, moved to upstate New York. I spent the better part of the pandemic poring through them and then collating all this material. Did I mention photographs? There are thousands of those, too, that neither my mother nor my father had the decency to organize into albums. And 16mm home movies.

I realize that this fetish for organization isn’t for everyone. A reasonable argument can be made that one's time can be better spent than on deciding whether an undated photograph from a children’s birthday belongs in an envelope marked 1962 or 1963.

But the process offers rewards beyond the psychic satisfaction of putting things in their proper place. It’s a hedge against mortality. That was my mother’s motivation. “Am very glad that I am keeping a diary,” she wrote. “Everything passes so quickly and one can hardly remember after a while. This way there remains something.”

The exercise of assembling all this stuff for the purposes of memoir writing provides an unanticipated benefit. It teaches one humility. Specifically, it forces you to reconsider the process of memory. You come to realize that your memories, no matter how stark or vivid, change and evolve over time. They get embroidered. They transform from fact into, if not quite fiction, a story that you tell yourself that fits neatly into the narrative of your life.

I could have sworn that when I returned home triumphant on May 13th, 1964, after winning the fifth grade Browning School field day trophy, I persuaded my admiring parents to double my allowance to 50 cents so that I could afford the double issue of Mad magazine then on newsstands. Except that an online search suggests that Mad didn’t publish a double issue in April, May or June of 1964. Maybe it never did. And a single issue cost only a quarter. I must have made the story up.

I have a vivid memory of returning home from school on Nov. 22, 1963, and breaking the news of President John F. Kennedy’s assassination to my mother. Her diary — ironically she rued how easy Jackie Kennedy’s life was compared to hers just the previous day — largely validates my recollection. Except that I wasn’t alone when our housekeeper answered the doorbell. My mother writes that she was thinking of doing some errands “when Ralphie and Johnny came home from school and told me that President Kennedy was dead, that he had been shot! I thought that they were kidding. So Ralphie told me to turn on the television.”

In my memory, I broke the news to her alone. My younger brother Johnny played no role. He wasn’t even there. Same thing when I attended Leonard Bernstein’s Young People’s Concerts at Lincoln Center on Saturday mornings in the mid-'60s.

As entertaining as the concerts were, and as brilliant as Bernstein was at bringing the music alive for children, today I see them through the prism of childhood angst and alienation. (By the way, I’m not fishing for sympathy that I was obligated to attend the maestro’s shows.)

My most vivid memories aren’t of the concerts but of having to dress up in a jacket and tie on a Saturday and then walking home alone up Central Park West, the light as stark and isolating as an Edward Hopper painting. My only solace was that I dropped by a drug store on the way and loaded up on candy bars.

But according to my mother’s diaries, I wasn’t alone; I was joined by two of my three younger brothers. If there’s an unmistakable thread here it’s that I’m the solo star of my own movie.

Writing a memoir offers the opportunity to put your life in perspective and exfoliate your memory. Whether you get it published or not, that’s reason enough to pursue the effort.

Thanks so much! Incorporating her writing is much of the reason I’m working on a memoir.

If I could give your mother's excerpt from her diary 1000 hearts I would. Simply wonderful! Ralph, I'm sure you considered this, but a compilation of her writings should be published and shared. A joyful treasure.