Every passport tells a story

The arrival of my new travel document triggers feelings of irrational exuberance

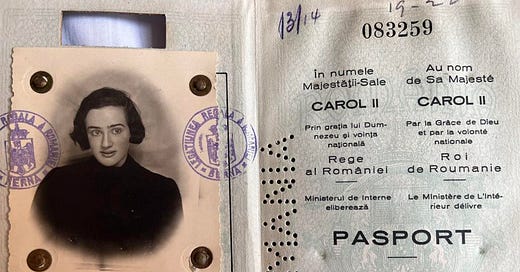

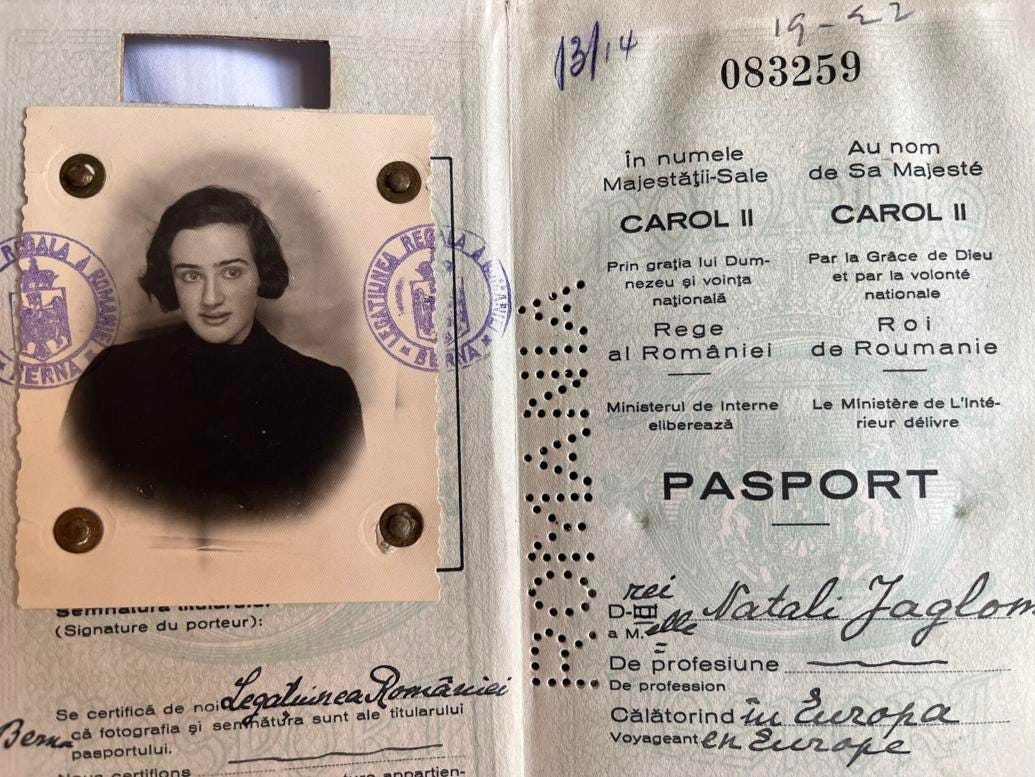

My mother’s 1930’s Romanian passport

I wanted to share some big news. My new passport arrived a couple of weeks ago. I’d been concerned. Instead of paying a few bucks extra to have the process expedited I decided to go the “routine” route and it took the full six weeks, if not longer for it to arrive in the mail.

Fortunately, I had no immediate travel plans so it wasn’t a big deal. But considering the horror stories I’ve heard about understaffed federal agencies I feared I might still be waiting in October when I plan to attend a family wedding abroad.

There are some that may consider a new passport — despite its laser engraved black and white photo image, and counterfeit-resistant multilayered plastic data page — unworthy of over-reaction. Perhaps equivalent to that scene in 1979’s “The Jerk” where Steve Martin as the Jerk loses it when the new phonebook arrives. “The new phonebook’s here! The new phonebook’s here!” he raves. “Page 73. Johnson, Navin R. I’m somebody now.”

I might not have exhibited Navin-like excitement but for a couple of recent developments. For starters, I inherited a bunch of family passports a few years back; approximately 40 of them dating back to the 1930s. A less sentimental person would have thrown them out with the trash.

But as I kept coming across more and more of them while emptying my parents apartment I decided to gather them in a storage box for posterity’s sake. My last cancelled passport now enters that collection. If nothing else they serve as eloquent testimony to the passage of time. Not to mention evolving passport design. I can watch my parents, my brothers and me grow from childhood to old age with each new passport and its updated photograph.

The second development was watching Ken Burns’ PBS series “The U.S. and the Holocaust,” where he documents the red tape the State Department drew to deny Jews admission to the United States during World War II, dooming many to death in Hitler’s concentration camps.

My family was among the fortunate ones who made it out. I’m not sure how they surmounted those hurdles, and anybody who can definitively answer the question is long gone. Money may have had something to do with it. My mother arrived in the United States aboard the “Queen Mary,” along with her father and younger sister on April 21, 1939, a few months before the war started.

I’d questioned her over the years about the intricacies of how she got here but she was only 14 at the time and vague about the details. She remembered a few things, however. For example, that the family was traveling on her father’s Polish visa even though he wasn’t Polish.

“In order to get to the United States it depended also from the papers on where you were born,” she remembered in a 2018 interview I recorded with her. “For him, for some reason, he had a Polish paper so he could come with Jeanie and me to New York. My mother, who traveled under a Romanian quota, couldn’t come straightaway here. She had to go to Canada first and she was there six months, and while she was there she submitted for entry here. But when you think of it, what was going on in the world at that time, we were so lucky.”

Their passports serve as evidence. There’s my mother’s visa, issued by the American counsel in Switzerland, where she attended boarding school, in black and white. She’s listed as “No. 5699 Polish quota” for which her family paid a fee of 10 U.S. dollars or rather the equivalent in Swiss francs.

Yet who knows how many strings were pulled and money passed under the table? I also found a cryptic letter dated a year before the family immigrated to the United States. It comes from the Home Office in London — the family stopped there on the way to the United States — that reads in part, “I am directed by the [U.S.] Secretary of State,” that my grandfather, “should now apply for a visa.”

“And at that time,” my mother remembered of her halcyon Swiss boarding school days, where she said her schoolmates included the daughters of Marlene Dietrich and, shockingly, Hitler’s foreign minister, “the idea was that if you went to the United States you never expected to get back. It was like the end of the world.”

The previous year her parents — they were Russian but fled to Romania during the Russian Revolution — took a round-the-world trip to decide where they wanted to relocate as anti-Semitism was spreading across Europe. They chose the United States, the story goes, because its wide open spaces reminded them of Russia. I have grainy photographs from that trip, among them one of my fashionably dressed grandmother standing alongside a towering cowboy — I suspect their tour guide — somewhere in the American West.

A passport can only tell you so much. Apart from ones’ sex and date of birth it’s just filled with immigration stamps — some of them barely legible if the customs agent neglected to replenish the ink — that document the name and date of the airport where you landed. But they’re evocative nonetheless. There’s the entry stamp at Shannon airport in Ireland the first time I set foot outside the United States at the age of 8. And another stamp, several passports later, documenting the month my wife and I spent in Kenya on our honeymoon.

But it’s those Romanian passports that bear the weight of history. Without them and the freedom they helped bestow I might never have existed, nor my slew of American passports, both canceled and new.

Good housekeeping suggests they ought to be consigned to the trash and eventually they probably will be, by my children or theirs. In the meantime they double as valuable family history. If you know how to read between the lines.

That's a wonderful story Ralph. However, it is a testament to the fact that if a person is born into wealth and prestige they have hit the life Lottery. Millions were not as fortunate as your mother and her family simply because they were not wealthy and they were not connected. Your example is the perfect example of how generational wealth ensures the success of a family and their progeny. It's nothing to be ashamed of but it is something to be aware of.

Unfortunately today many countries including the United States routinely neglect to stamp passports, often instead opting for a separate paper or nothing at all!